Source: depositphotos.com

Reading time: ten minutes

The COVID-19 pandemic and the effort made on behalf of governments to keep the situation under control led to astounding expenses for all nations across the globe.

In the first quarter of 2020, China’s economy shrank by 6.8% year-over-year. Soon, it was followed by the Eurozone, whose finances also shaved off 14.8% compared to last year, as well as by the U.S. with its year-over-year decline of 4.8%.

But perhaps none of this is as terrifying as the worst unemployment rates this world has ever seen—perhaps the highest since WWII. In this article, we will examine how unemployment looks like in different parts of the globe, as well as some strategies that governments could adopt in order to deal with this unprecedented scenario.

We may end up not witnessing pre-2020 employment rates again

According to the International Labor Organization of the UN, the global economy is in for a rough ride. In the organisation’s report, experts project that the pandemic will have a devastating financial effect on close to 1.6 billion employees in the grey market, while another 305 million people are expected to be left without work in the second half of 2020 alone.

Economists hope that the multiple financial grants, issued by both governments and central banks, will be enough to set economies back on track, as well as bolster employment rates. Ideally, this would enable those people who were either laid off or forced to take paid or unpaid leave to restore their previous work routines.

However, some experts worry that the inflicted reallocation shock on employment could lead to permanent damages for some companies—or even for entire industries. If this were to happen, laid off workers would find it much more difficult to get their previous jobs back due to a lowered market demand and this, in turn, would keep unemployment levels high.

“[There will be] well into the millions of people who don’t get to go back to their old job. In fact, there may not be a job in that industry for them for some time.”

Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve

One solution here could be to retrain and relocate employees until employment levels are balanced on a per-region basis. This task, however, could prove to be too costly and difficult for both the unemployed and their governments, the latter of which would also have to invest in safer and more sophisticated social systems in order to make it all work.

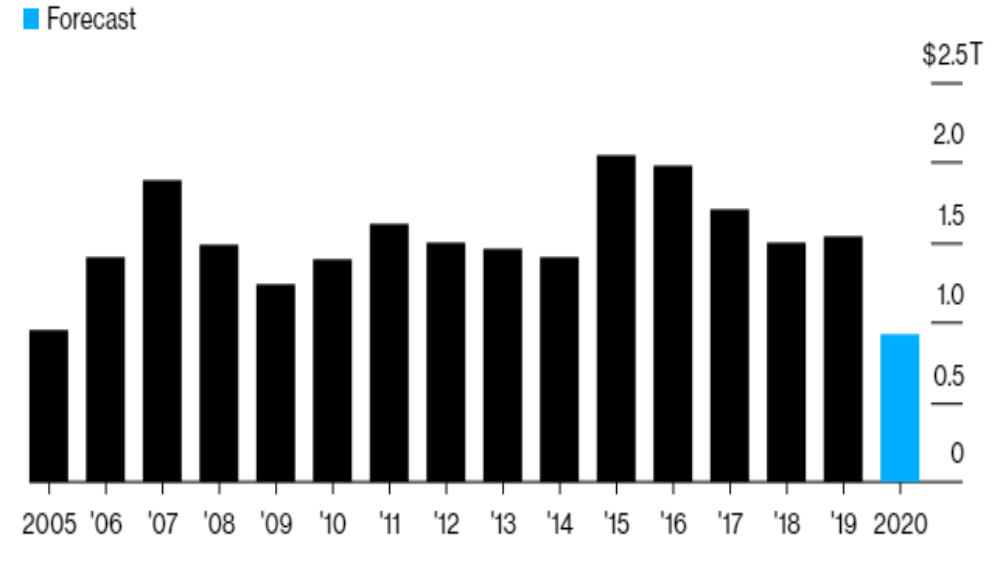

Unemployment leads to a decline of foreign direct investments

According to another UN report, foreign direct investments (FDI) for this year are expected to dip by 30% to 40% on a global scale due to the coronavirus pandemic. This trend is projected to continue throughout 2021 as well. This sharp decline from $1.54 trillion in 2019 to under $1 trillion happens for the first time since 2005.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

Some experts think that we might see early signs of recovery no sooner than in 2022. This shortage of funds will be felt the most by developing countries. Meanwhile, the imposed lockdown measures will force international companies to re-evaluate their business practices. Five thousand of the world’s leading businesses have already reported that their latest quarterly earnings have slumped by 40% on average compared to what was projected, and some industries even reported losses. Weaker profits could lead to weaker reinvestments which, in turn, make up a little over 50% of the global FDI.

“Flows to developing countries will be hit especially hard, as export-oriented and commodity-linked investments are among the most seriously affected [by COVID-19]. The consequences could last well beyond the immediate impact on investment flows.”

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres

According to the UN report, in the years following the inflation, the focus might shift from manufacturing processes on a regional level to ones on a local level. The competition amongst those businesses that wish to benefit from the shrinking FDI pool will also become more fierce. Many companies will probably also try to diversify their suppliers.

How unemployment looks like in different countries

The U.S.

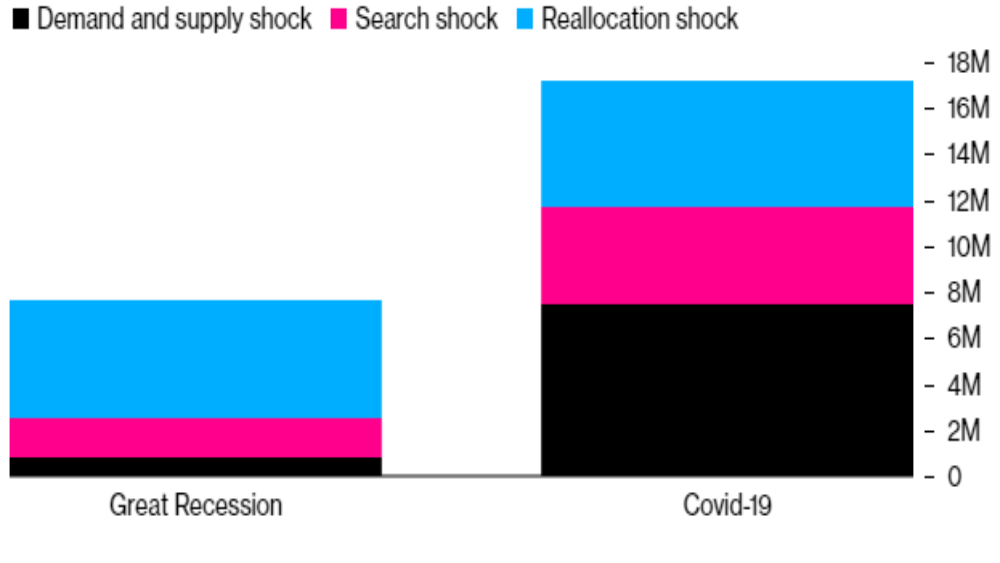

In a study done by Bloomberg Economics, in the six weeks leading to 25 April 2020 close to 28 million Americans have made unemployment claims. In the words of experts, at least 30% of these layoffs are attributed to the so-called reallocation shock—an event that was last observed during WWII. In essence, a reallocation shock is expressed through the hectic training and reassignment of redundant personnel by governments and private companies.

“There’s a massive reallocation shock. . . . [The recession] hits different sectors differently. Some benefit and some fall.”

Nicholas Bloom, Professor of Economics at Stanford University

What’s more, due to the intensifying COVID-19 outbreak, the Federal Reserve projects to leave interest rates unchanged (close to zero) at least until 2022.

Unemployment data in the U.S. for 2020 | Source: Bloomberg Economics

In the report, it is also projected that unemployment in the U.S. will begin to rapidly recover. However, this growth will be short-lived and, once it’s over, there will still be millions of people left without work.

Among the most vulnerable jobs in the country are those found in the hospitality sector, as well as in the retail, entertainment, healthcare, and education sectors. In some cases, the pandemic could further hurt the income of brick & mortar stores whose chances of selling their products are now even slimmer compared to leading e-commerce giants like Amazon.

Research published in May by the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago estimated that 42% of the recent layoffs in the U.S. are projected to be permanent.

Canada

According to data from the country’s official statistics bureau, the unemployment rate for April was 13%—a 5.2% boost compared to March. By May 2020, more than 7.2 million Canadians have requested emergency unemployment assistance.

Japan

Unemployment in the land of the rising sun has been growing slower compared to other G-7 members. In March, the unemployment rate was reported at 2.5% or 1.76 million people—”only” 20,000 more than the rate observed for the same period in 2019. Despite that, job openings in the country are at their lowest in three years and an increasing number of people are requesting emergency loans due to wage cuts or lack of any income.

Europe

According to statistical data for June 2020 published by Eurostat, the Statistical office of the EU, the region’s quarter-on-quarter GDP growth abruptly fell to -3.6% during the first three months of 2020 compared to the positive growth of 0.1%, reported for the last quarter of 2019. Among the most affected countries are Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands.

As far as the unemployment rate is concerned, the total percentage of unemployed people in the region grew to 7.3% in April, or a 0.2% increase compared to March. This means that, in April, close to 397,000 people in the European Union have lost their jobs. In relation to this, on June 8th the Governing Council of the European Central Bank declared that it will preserve its benchmark-refinancing rate at 0.0 % which it has kept since 2016.

Let’s take a closer look at how some of the EU members are tackling unemployment.

United Kingdom

Close to 2 million people have applied for the main benefit, called Universal Credit, since the nation enacted lockdown measures to combat the spread of the coronavirus. A quarter of the employed workers in the U.K. has registered for the government’s job retention scheme, which covers 80% of their monthly wages.

Right now, financial forecasts for the country are rather gloomy, especially when it comes to the aviation sector where many airlines, British Airways included, have been forced to lay off a significant portion of their personnel (close to 12,000 jobs in the case of BA).

Ireland

In Ireland, the budget air travel company Ryanair declared that it will lay off 15% of its global workforce (about 3000 jobs) after COVID-19 firmly rooted the airline’s fleets in place.

France

In May, close to 10 million people in the French private sector were financially supported by the state through a partial employment scheme, called chômage partiel.

“That’s more than one employee out of two, and six companies out of 10.”

Muriel Penicaud, French Labour Minister

Among the French companies with the highest workforce cuts is no doubt Renault, which in May laid off 15,000 workers globally. The cut is cited as a necessary measure to fulfil the company’s plan of securing €2 billion in savings over the next three years. The French president Emmanuel Macron did try to appease the disgruntled workforce by promising employees in two Renault factories that their future there was secure.

Germany

The unemployment rate in Germany is climbing at a significantly slower tempo compared to countries like the U.S., in part due to the government scheme of subsidising the wages of struggling employers and employees on short-time work programmes (the so-called Kurzarbeiters). However slow, the unemployment rate does keep on rising, reaching 373,000 unemployed persons in April.

Italy

In March, the unemployment rate in Italy dropped to 8.4%—its lowest level in almost nine years. The government attributed this to the fact that the active job seekers for March fell by 267,000 compared to the previous month—completely plausible seeing that the unemployment rate is measured based on the number of currently active job-seekers. The Italian Economy Minister Roberto Gualtieri stated that the government has pledged around €75 billion in support of families and companies affected by COVID-19.

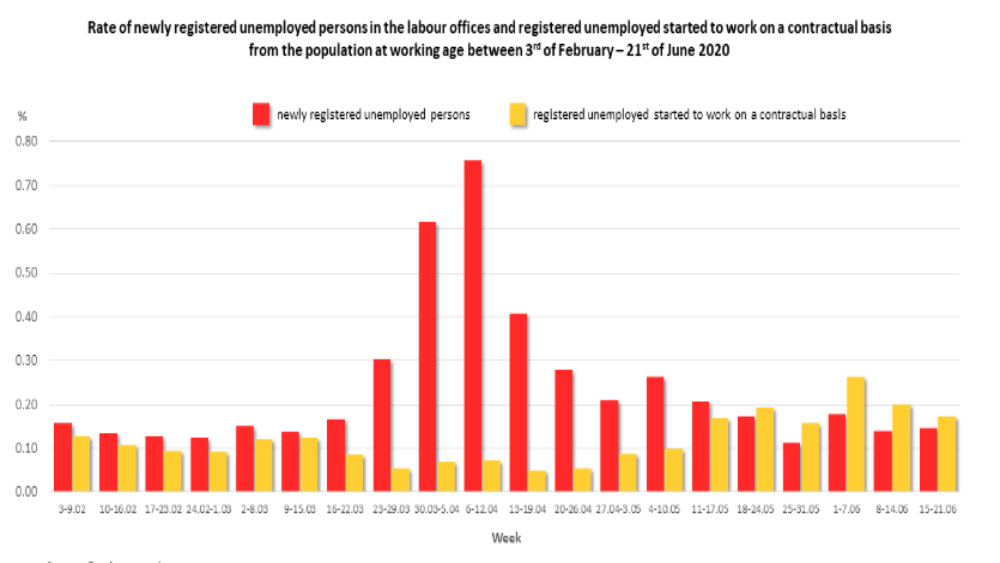

Bulgaria

Data from the nation’s Employment Agency revealed that the number of newly registered unemployed persons between February 3rd – June 21st was 188,525. However, 99,523 previously unemployed persons began working on a contractual basis in the same period.

Source: Bulgarian Employment Agency

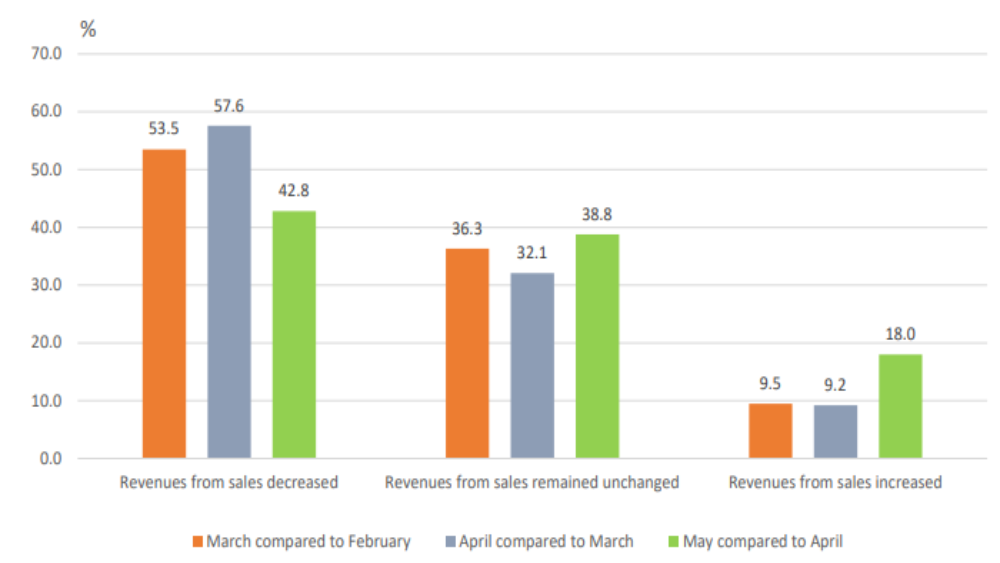

In May, the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria did a second short business survey with several non-financial enterprises to gauge the effect of the declared state emergency on the nation’s most affected economic sectors.

Source: National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria

The study showed that 42.8% of the surveyed enterprises declared a decrease in revenues from sales of goods and services in May compared to April 2020, 38.8% declared no change, and 18.0% declared an increase.

The breakdown by economic sectors showed that 54.8% of the non-financial enterprises in the arts, entertainment, and recreation sectors, as well as those offering repair of household goods and other services, experienced a decrease in revenues from sales of goods and services. For the industrial production sector this share was 46.8%, for the construction sector—39.3%, and for the trade, transportation, and foodservice sectors—40.8%.

For June, 93.2% of the surveyed non-financial enterprises expect that they will continue their current business operations, 3.8% expect to temporarily cease their activities, while 1.6% project to permanently shut down their businesses.

The pressure on governments to act is rising

Source: unsplash.com | Photographer: Nick Romanov

At the moment, governments are working round-the-clock to provide solutions that could help bigger companies survive and employees—to find new work opportunities. At the same time, extra care is taken to avoid incentivising companies whose recovery is no longer possible and which, at this point, only drain resources.

In a study done by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, it was stated that the unprecedented shock of the virus may force governments to put in twice the effort in order to protect businesses and the workforce compared to a “regular” recession.

The main problem here is that no one-size-fits-all solution for economic problems related to COVID-19 really exists as different reasons behind the job cuts will require different (and sometimes contradictory) political approaches. Experts also warn that the end of the anti-coronavirus measures could usher in another redistribution shock if consumer preferences recover quickly enough for companies to start recruiting again.

The other important issue is that, with the increase of permanently lost jobs, more and more unemployed people will gradually lose their permanent skills, which would further boost unemployment rates—a phenomenon economists call “hysteresis”.

In relation to the latter, according to Sharan Burrow, the General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation, the pandemic “has exposed the fault lines that already existed for working people and the economy.” He also mentioned that achieving the “new normal” in terms of employment rates will “require a new social contract between governments and their citizens with the backing of the international community.”

Based on what is happening now, labour market experts believe that these measures should not be limited to improving financial security systems alone, but should also ensure that the positions held by employees reflect their actual skills. One potential solution, proposed by economists at the Peterson Institute, is to introduce subsidies on employees’ salaries in order to speed up the recovery of manufacturing processes in times of a crisis.

In addition, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development called for public investment initiatives, aimed at training or retraining unemployed workers. The organization’s idea is to prepare employees for the next phase of the technological revolution—a process that is mercilessly advancing at a time when more and more companies, from manufacturers to retailers, are forced to adapt to the harsh conditions of the post-viral world by making job cuts.

***

Looking to trade on the global markets, but have little to no experience? Open a demo account in Delta Trading and test your boldest strategies in a real market environment, without any risk of losing your actual funds.